This particular class was a room of twenty Rwandan girls, ages 13 to 19, who come from vulnerable families living in the slums of Kigali. They are students at MindLeaps where I began teaching classes this past spring.

Thanks to the generosity of the Alice Rowan Swanson fellowship grant program awarded through Students for International Training (SIT), I was able to launch a comprehensive sexuality curriculum for MindLeaps, which was piloted for four months with a group of twenty Rwandan girls. The program emphasizes confidence building and communication skills, putting youth at the center of their sexual health and giving them the tools and confidence to make healthy, informed choices.

Fast forward to one of our last classes and the feel of the class is markedly different. We’re exploring communication techniques and I’m trying to teach “I Messages” (statements like “I feel angry when you ___” rather than “I hate you! You’re a horrible human!”) using role play scenarios. The first role play hilariously got the girls out of their comfort zone as it required one actor to pretend to be a six-year-old child who was constantly getting into their older sibling’s things and the older sibling had to communicate their feelings about it. The following role play depicted a young woman asking her mother for money to buy sanitary pads for the first time. The girls responded beautifully with statements like, “Mom, this feels embarrassing for me to say, but I really need money to buy pads,” and the mother responding in kind, “Thank you for coming to me; let’s talk about your period so you know what to expect.” Another role play was where one partner shared that they like the other person, but that person has to respond that they’re not interested in pursuing a relationship. This was also delivered using “I Messages” and went something like this:

Person 1: Hey, I like you! You’re real cute!

Person 2: That’s really sweet, but I’m not interested in being your girlfriend.

Person 1: What? Why??

Person 2: I’m just not ready for a relationship right now. How about we just be friends?

Person 1: Ok, that’s cool.

[They walk off, arm in arm.]

For such generally shy, tight-lipped girls, the forwardness of their role-plays and the strength of their statements were really powerful to witness. The students admitted that these conversations would definitely be harder with actual mothers and actual boys, but they’ve practiced saying the words, and the statements themselves are normalized—these are awesome steps.

Other highlights from our nine weeks together included a gender equality game, where relay teams competed in tasks stereotypically considered “women’s work.” We all had several laughs when we got the boys to try the same tasks, but the game was an effective way to jumpstart a discussion on gender equity and stereotypes.

Another highlight was seeing the increasing boldness of student questions. Through the anonymous “Question Box”, where students have a chance after each class to ask an anonymous question about sexual health, I was asked the radical-for-Rwanda question of “How can I enjoy sex without having children?” and the tricky question of “What happens when a boy impregnates you and then starts yelling at you?” These were invaluable opportunities to promote open communication, discussion of family planning, and long-term goal setting—all critical values of the program.

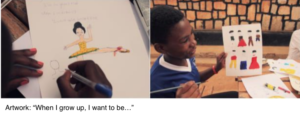

In August, we had the honor of showcasing the program to the famous Misty Copeland, the first African American woman to become a Principal Dancer at the American Ballet Theatre. MindLeaps hosted a celebration day, where participants used dance, painting, poetry, and theater to reflect on what they had learned in the program. One student presented her artwork, which depicted two women—one doing stereotypical “woman’s work” and the other working on a computer and pursuing a career. She explained that it’s important for women to have the chance to pursue their dreams and create a future for themselves. Other girls painted adult versions of themselves as leaders, professional dancers, and doctors—indicating that they’re thinking about their futures and how their sexual health choices can impact those futures.

At the end of the celebration day, we presented certificates to each participant and a reusable menstrual pad kit, provided by Days for Girls and made by local Rwandan women. The partnership with Days for Girls provides our vulnerable girls with an invaluable resource. The high cost and embarrassment of buying pads present challenges for consistent good menstrual hygiene, particularly for families living in poverty.

Check out this amazing video produced by Misty’s team about the event

In late September, we pilot a boys’ class covering the same material. The girls are embarrassed that their male classmates will be learning about female anatomy—“Do you have to teach them about the vagina?” And there are also discussions on expanding this program to another MindLeaps Center in Guinea in 2019.

I have high hopes for the continued implementation and development of this program, and I feel honored to have been a part of these girls’ lives. Thank you to the Alice Rowan Swanson fellowship for providing the necessary funds to launch this program, to Our Whole Lives (a comprehensive sex ed program in the US) that provided crucial support to the curriculum’s development, to Days for Girls for providing awesome and fun reusable pads, and to Misty Copeland for her promotion of this important work. Let’s continue to increase access to comprehensive reproductive health education and services!